Foam rollers are often present in fitness centers, physio centers, and home workout kits due to their affordability and portability factors. They are applied to self-myofascia (SMR). Precise foam rolling can accelerate your healing in case you are an athlete, a runner, or an office worker who spends most of his/her time sitting down. It may also enhance your motion spectrum, reduce the pain and assist you to revert to comfortable motions. Research has advanced over the last decade and has produced positive effects of short-term improvements in mobility and recovery with its correct usage.

What is foam rolling?

Definition: Self-Myofascial Release (SMR)

Foam rolling is a form of self-myofascial release (SMR) that applies sustained pressure and slow rolling to muscle and fascial tissue using a foam cylinder (roller), textured roller, vibrating roller or small massage ball. The goal is to reduce localized muscle tightness (trigger points), improve blood flow and temporarily alter the nervous system’s sensitivity to allow better muscle length and joint motion.

How Do Foam Rollers Work on Muscles and Fascia?

While popular descriptions often say foam rolling “releases fascia,” most evidence suggests the primary effects are mechanical pressure, increased circulation, and changes in the nervous system’s pain and stretch tolerance leading to improved range of motion (ROM) and reduced perceived soreness [1]. In short: foam rolling influences tissue mechanics and neuromuscular control rather than permanently “unsticking” fascia the way a therapist might.

Types of Foam Rollers

- Standard smooth roller: Good for beginners and general use.

- Textured/trigger-point roller: Ridges and knobs provide deeper pressure to local knots.

- Vibrating foam roller: Adds vibration to enhance circulation and pain reduction for some users. Early research shows extra benefit for soreness and perceived recovery with vibration.

- Half-round roller (soft): Stable and beginner-friendly; useful for rehab and balance work.

Choosing a roller depends on your tolerance (softer for sensitive users, firmer or textured for advanced users).

Benefits of Foam Roller Exercises

Improved Flexibility and Range of Motion

Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that foam rolling produces short-term increases in joint ROM (e.g., improved hamstring or hip mobility) without impairing muscle strength making it a useful warm-up tool. In many studies, noticeable ROM gains occur within seconds to a couple minutes per muscle.

Faster Muscle Recovery After Workouts

Foam rolling post-exercise can reduce the symptoms of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and help preserve strength and power after intense training [2]. Some trials indicate that repeated post-exercise rolling (e.g., 20 minutes post-workout and daily thereafter) reduces tenderness and helps athletes recover quicker.

Pain Relief from Tight Muscles and Knots

Using a roller to pause and breathe into a tender spot (30-90 seconds) often lowers perceived pain and sensitivity in that spot. This analgesic effect helps people mobilize stiff joints and use muscles through fuller ranges.

Better Circulation and Reduced Inflammation

By applying pressure and moving tissue over time, foam rolling can increase local blood flow and lymphatic return, which supports metabolic waste removal after workouts, a mechanism that contributes to recovery. Emerging research also suggests short-term reductions in markers of muscle soreness and fatigue.

Improved Posture and Injury Prevention

Regular foam rolling paired with strengthening and mobility work helps maintain muscular balance around the hips and spine, supporting better posture and reducing risk of overuse injuries for example, helping runners maintain hip mobility to avoid IT-band or knee complaints [3].

Stress Relief and Relaxation

Longer, slower rolling sessions (or paired rolling and breathing drills) can reduce sympathetic arousal (stress response) and promote relaxation, useful on recovery or low-effort days.

How to Use a Foam Roller Safely?

General Safety Tips and Precautions

- Start gently. Use lighter pressure and build up intensity; aggressive rolling can bruise or cause microtrauma.

- Avoid rolling directly on joints or bony prominences. Roll muscle bellies to protect structures.

- Don’t force severe pain. Discomfort is expected when working trigger points, but sharp or radiating pain is a warning sign.

- If you have a medical condition (recent fracture, deep vein thrombosis, severe osteoporosis, acute inflammation) check with a clinician before using a roller.

Correct Posture and Technique While Rolling

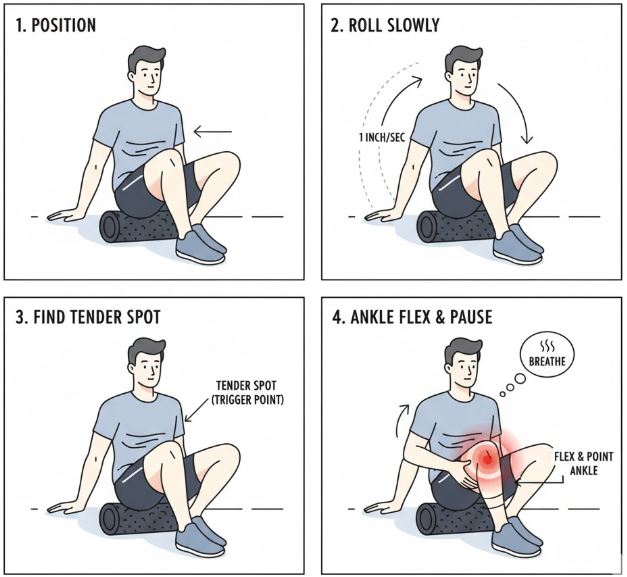

- Keep the roller perpendicular to the muscle and move slowly (about 1 inch per second).

- Support your body with hands/legs so you can control pressure.

- When you hit a tender spot, pause and gently breathe into the spot for 20-90 seconds while performing small movements (e.g., point/flex ankle while rolling the calf). This “sustained pressure + active movement” helps more than passive rolling alone.

Duration and Frequency Recommendations

- Time per muscle group: commonly suggested 30-90 seconds per area; some studies find 60-90 seconds gives measurable ROM benefits. Short warm-up passes of 20-30 seconds are also effective to “wake up” tissue before activity.

- Frequency: 3-7 times per week is common in practice; daily light rolling is safe for most people if it doesn’t increase pain. Deeper, longer sessions should be used sparingly.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Rolling too fast – reduces effectiveness.

- Putting full body weight on very tender spots – can aggravate tissue.

- Rolling the lower back directly – this risks forcing the lumbar spine into unsafe positions. Use a lacrosse ball or therapist for spinal regions and roll the muscles on either side of the spine, not the spine itself.

Foam Roller Exercises for Different Muscle Groups

Below are safe, effective examples. For each exercise, move slowly and focus on breathing.

1. Upper Body

Thoracic spine mobilization (upper back):

- Lie on your back with the roller horizontal under the mid-back. Support your head with hands, extend over the roller and roll 2-4 inches up/down between the shoulder blades. This helps thoracic mobility and posture. (Avoid the lower back.)

Lats and shoulders:

- Lie on your side with the roller under your armpit, extend your arm and roll from armpit to mid-rib area to release the latissimus dorsi and posterior shoulder. Good as part of pre-run or post-upper-body sessions.

Pectoral release (chest):

- Place a softer roller or ball under the chest/pectoral area and perform slow rotations with the shoulder to open the chest.

2. Lower Body

Quadriceps:

- Face down, roller under thighs. Support with forearms and roll from hip to just above the knee; pause on tight spots and perform slow knee flexion/extension to activate the muscle.

Hamstrings:

- Sit with the roller under your hamstring, hands behind you for support. Lift hips and roll from glutes to just above the knee. Hold over tender spots and contract/relax the hamstring.

Calves:

- Sit with the roller under your calves. Lift hips and roll ankle to just below knee. Point and flex your foot while pausing on sensitive spots. This is especially useful for runners.

Glutes and piriformis:

- Sit on the roller with one foot crossed over the opposite knee and roll the glute area. The piriformis can be sensitive; use less weight and a smaller ball if painful.

Hip flexors:

- Lying face down, place the roller under the front of the hip and move gently; use your arms for support to control pressure.

3. Core and Posture

Lower back (with caution):

- Avoid rolling the lumbar spine directly. Instead, do thoracic mobilizations and roll hips/glutes to relieve tension that refers to the low back. For small, targeted pressure along paraspinal muscles use a small lacrosse ball while avoiding direct spine pressure

IT band / lateral thigh:

- Roll the outer thigh from hip to just above the knee. Many coaches recommend pairing IT-band rolling with hip/glute activation because the IT band itself is connective tissue and benefits more from adjacent muscle release and strengthening than aggressive rolling.

4. Recovery and Relaxation

Neck and traps (use smaller tools):

- Use a small massage ball or softer half-roller for upper traps and neck; avoid compressing the front of the neck, and always keep movements controlled.

Plantar fascia (foot rolling):

- Sit and roll a small ball or half-roller under the foot arch for 30-60 seconds to relieve plantar tightness, a popular exercise for runners.

Foam Roller Routines for Specific Needs

Warm-up Routine (5-8 minutes)

- Light cardio for 3-5 minutes.

- Quick foam-roll passes (20-30 sec each) for calves, quads, glutes, and thoracic spine.

- Finish with dynamic mobility (leg swings, inchworms). This primes tissue and increases ROM without decreasing strength.

Cooldown/Recovery Routine (10-20 minutes)

- After training, spend longer (60-90 sec) on tight spots: quads, hamstrings, calves, and glutes. Combine with deep breathing and gentle stretching. Some evidence suggests 20 minutes post-workout and daily follow-up can reduce DOMS [4].

Runners & Endurance Athletes

- Emphasize calves, quads, IT band (with adjacent hip work), glutes and plantar fascia. Small daily sessions (5-10 minutes) help maintain flexibility and reduce injury risk.

Desk Workers / Posture Correction

- Focus on thoracic mobilizations, lats, and hip flexors to counteract hours of sitting. A short nightly routine (5-10 minutes) helps posture and reduces morning stiffness [5].

Sports-specific Drills

- Pair foam rolling with sport drills, e.g., quick pre-game rolling + dynamic warm-up for soccer or basketball. Use targeted rolling to free up hips and calves for better sprinting mechanics.

Comparing Foam Rolling with Other Techniques

Foam Rolling vs. Static Stretching

Recent meta-analyses show foam rolling and static stretching produce similar short-term improvements in ROM [6]. However, foam rolling often provides the additional benefit of reducing soreness without reducing subsequent muscle performance, making it an attractive option when both mobility and performance matter. For warm-ups, many practitioners prefer dynamic stretching or rolling combined with movement.

Foam Rolling vs. Massage Therapy

Hands-on massage by a therapist can provide deeper, skillful release and is useful for complex or severe issues. Foam rolling is an accessible, low-cost self-help tool that complements professional care and daily maintenance. For many users, rolling is an effective daily maintenance strategy, while occasional professional massage addresses deeper chronic issues.

Complementary Use: Combining Stretching & Foam Rolling

Best practice: use short foam rolling passes to increase tolerance and ROM, then perform targeted static or dynamic stretches and strengthening exercises in that new range. This sequencing supports longer-term mobility gains by reinforcing strength through the increased ROM.

Expert Tips for Maximizing Benefits

- Breathe slowly and deeply while holding on trigger points.Breathing helps the nervous system relax.

- Roll slowly (≈1 inch/sec). Fast rolling reduces efficacy.

- Progress the roller: start with softer/full-radius rollers, then introduce firmer or textured rollers as tolerance improves.

- Combine with strengthening: rolling alone won’t fix muscular imbalances; pair SMR with targeted strengthening (glute activation, hamstring/quadriceps work) [7].

- Use vibration thoughtfully: vibrating rollers may amplify pain relief and recovery for some users, but pick settings that don’t cause discomfort.

Conclusion

Studies have shown that foam rolling is an affordable, fairly effective, and convenient technique to enhance short-term movement, reduce pain, and accelerate healing process from injury. When used in a proper manner and over a long duration, foam rollers will assist athletes and frequent exercisers remain at optimum body function and alleviate pain when used together with building and mobility exercises. The proper way of correctly using it includes the usage of the right level of force and pre-planned programming. If you have a complicated injury or chronic pain, you must consult a physician for better treatment.

Lifestyle factors are often the primary cause of chronic pain. Know how:

Frequently Asked Questions:

1. What are the best foam roller exercises for beginners?

Start with thoracic spine mobilizations, calves, quads and glutes using a soft- to medium-density smooth roller. Aim for 20-60 seconds per area, keeping pressure light and focusing on slow movement and breathing. Build duration and intensity as tolerance improves.

2. How often should I use a foam roller for muscle recovery?

Daily light rolling is safe for most people. For deeper recovery sessions (longer holds on trigger points), 3-5 times per week is common. Pay attention to tissue response; if soreness worsens, reduce frequency or intensity.

3. Can foam rolling replace stretching?

Not entirely. Foam rolling and stretching often produce similar short-term ROM improvements, but each has unique benefits. Use foam rolling to reduce soreness and prepare tissue; use dynamic stretches in warm-ups and static stretches for longer flexibility goals. Combining both is often best.

4. Is foam rolling safe for lower back pain?

Avoid rolling the lumbar spine directly. Instead, roll the glutes, hamstrings, thoracic spine and hips. If you have chronic low-back pain, consult a clinician targeted therapy or small ball work on either side of the spine may be more appropriate than full lumbar rolling.

5. What type of foam roller is best for athletes?

Athletes often combine rollers: a firmer textured roller (for deep trigger-point work), a medium smooth roller (for general maintenance), and a half-roll for mobility drills. Vibrating rollers can help some users with recovery, but choose what feels best and doesn’t induce excessive pain.

———

Why betterhood?

Because muscle and joint pain gradually robs you of your freedom to do what you love.

We build science-backed tools for posture, support, pain relief, recovery – so your muscles, bones, and joints stay strong for life.

Live better. Live Pain-Free. With betterhood.

———

References

- Cole, G. (2018). The evidence behind foam rolling: a review. Sport Olympic Paralympic Stud J, 3, 194-206. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gibwa-Cole-2/publication/328474367_The_Evidence_Behind_Foam_Rolling_A_Review/links/5bcfd18aa6fdcc204a035823/The-Evidence-Behind-Foam-Rolling-A-Review.pdf

- Wei, M., Liu, X., & Wang, S. (2025). The Impact of Various Post-Exercise Interventions on the Relief of Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness: A Randomized Controlled. Frontiers in physiology, 16, 1622377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2025.1622377

- Junker, D., & Stöggl, T. (2019). The training effects of foam rolling on core strength endurance, balance, muscle performance and range of motion: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of sports science & medicine, 18(2), 229. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6543984/

- Naclerio, F., Moreno-Perez, D., Seijo, M., Karsten, B., Larrosa, M., García-Merino, J. Á. L., … & Larumbe-Zabala, E. (2021). Effects of adding post-workout microcurrent in males cross country athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(12), 1708-1717. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1862305

- Strobl, P. Transform Your Nights: How to Design an Evening Routine That Supports Your Sleep and Productivity. Life, 1(832), 534-2480. https://confidecoaching.com/how-to-design-an-evening-routine/

- Konrad, A., Alizadeh, S., Anvar, S. H., Fischer, J., Manieu, J., & Behm, D. G. (2024). Static stretch training versus foam rolling training effects on range of motion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 54(9), 2311-2326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02041-0

- Madoni, S. N., Costa, P. B., Coburn, J. W., & Galpin, A. J. (2018). Effects of foam rolling on range of motion, peak torque, muscle activation, and the hamstrings-to-quadriceps strength ratios. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(7), 1821-1830. DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002468