A curious thing happens in the tunnel before an Olympic final. If you watch closely, not at the scoreboard, not at the athletes warming up, but at the way they walk, you’ll notice something remarkable. One sprinter bounces lightly, shoulders back, eyes scanning the stadium as if it already belongs to her. Another keeps their head down, movements tight, body folding in on itself like it’s trying to disappear.

By the time they reach the starting blocks, before a single muscle has fired in anger, you can predict with uncomfortable accuracy who will run like a champion and who will run like they’re being chased.

The Psychology of Gait

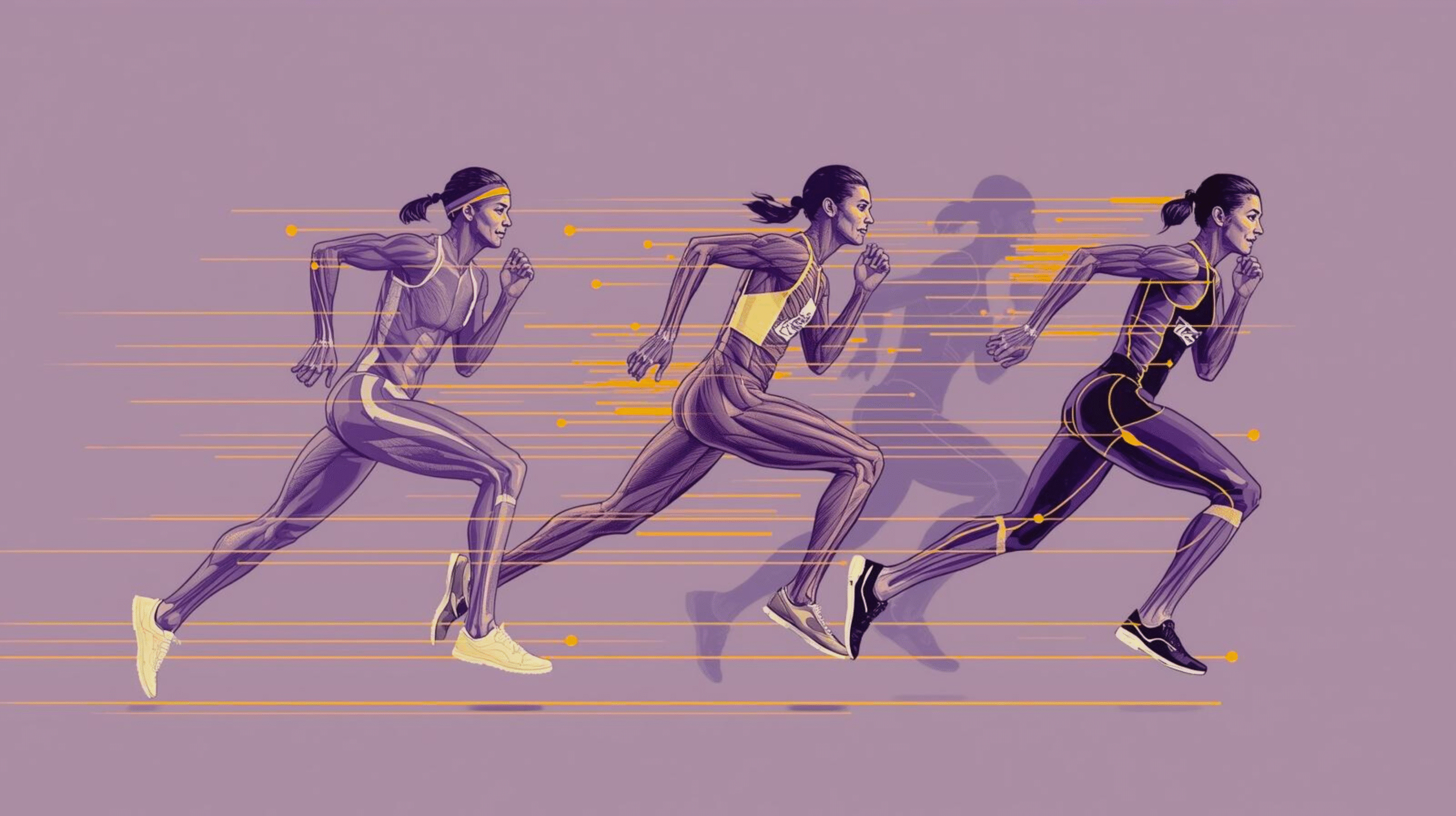

For centuries, posture was seen as a matter of mechanics: an upright back, squared shoulders, efficient stride. But modern neuroscience has added a provocative twist. How you carry yourself doesn’t just signal confidence, it creates it.

Studies at Ohio State University showed that people asked to sit upright while completing tasks reported higher self-esteem and greater persistence than those slouching. Another experiment found that adopting expansive postures (shoulders open, chest lifted) increased testosterone and decreased cortisol, even when participants weren’t aware they were “posing.” The body, in other words, is not just a mirror of the mind, it’s a sculptor of it.

Olympic athletes know this intuitively. They train gait and posture not only to conserve energy but to build an aura—around themselves and in the minds of their rivals.

The Silent Duel Before the Duel

Sports psychologists talk about the “pre-performance handshake.” Not literal handshakes, but the nonverbal negotiations that happen in the moments before competition. A boxer who walks slowly, eyes unflinching, sends a very different message than one who glances nervously at the floor. Opponents are watching. The crowd is watching. More importantly, the self is watching.

Take Usain Bolt. His famous swagger before a race wasn’t just showmanship. It was a neurobiological reset. By moving loosely, smiling, and expanding his posture, he kept his nervous system in a state of relaxed readiness rather than anxious overdrive. His body language told competitors: I’m not tense, because I know what’s coming.

Walking as Identity

This idea stretches beyond sport. Gait becomes a kind of identity loop. If you walk like a leader, you prime yourself to feel like a leader, and others are more likely to treat you as one. That reinforcement, in turn, deepens the identity. Conversely, a slouched, hesitant walk tells both your nervous system and the world: I’m uncertain here.

Anthropologists studying tribal dances have long noted that expansive, rhythmic movements bond groups together and establish hierarchy. The Olympic tunnel is no different. Walking becomes a kind of declaration—an embodied press release of confidence.

The Hidden Lesson

Most of us will never enter an Olympic stadium. But the lesson is uncomfortably transferable. The way you walk into a boardroom, step onto a stage, or even enter your own home sets off the same psychological cascade. Posture is not cosmetic. It is a conversation between you and your nervous system, between you and everyone who witnesses you.

So why do Olympic athletes walk differently? Because they understand that performance starts long before the gun fires. Their gait isn’t just efficiency of movement, it’s efficiency of psychology.

And maybe that’s the overlooked secret: before you can run like a champion, you have to learn to walk like one.

Co-authored by: Shayamal Vallabhjee

Chief Science Officer: betterhood

Shayamal is a Human Performance Architect who works at the intersection of psychology, physiology, and human systems design helping high-performing leaders, teams, and individuals thrive in environments of stress, complexity, and change. His work spans elite sport, corporate leadership, and chronic health and is grounded in the belief that true performance isn’t about pushing harder, but designing better.