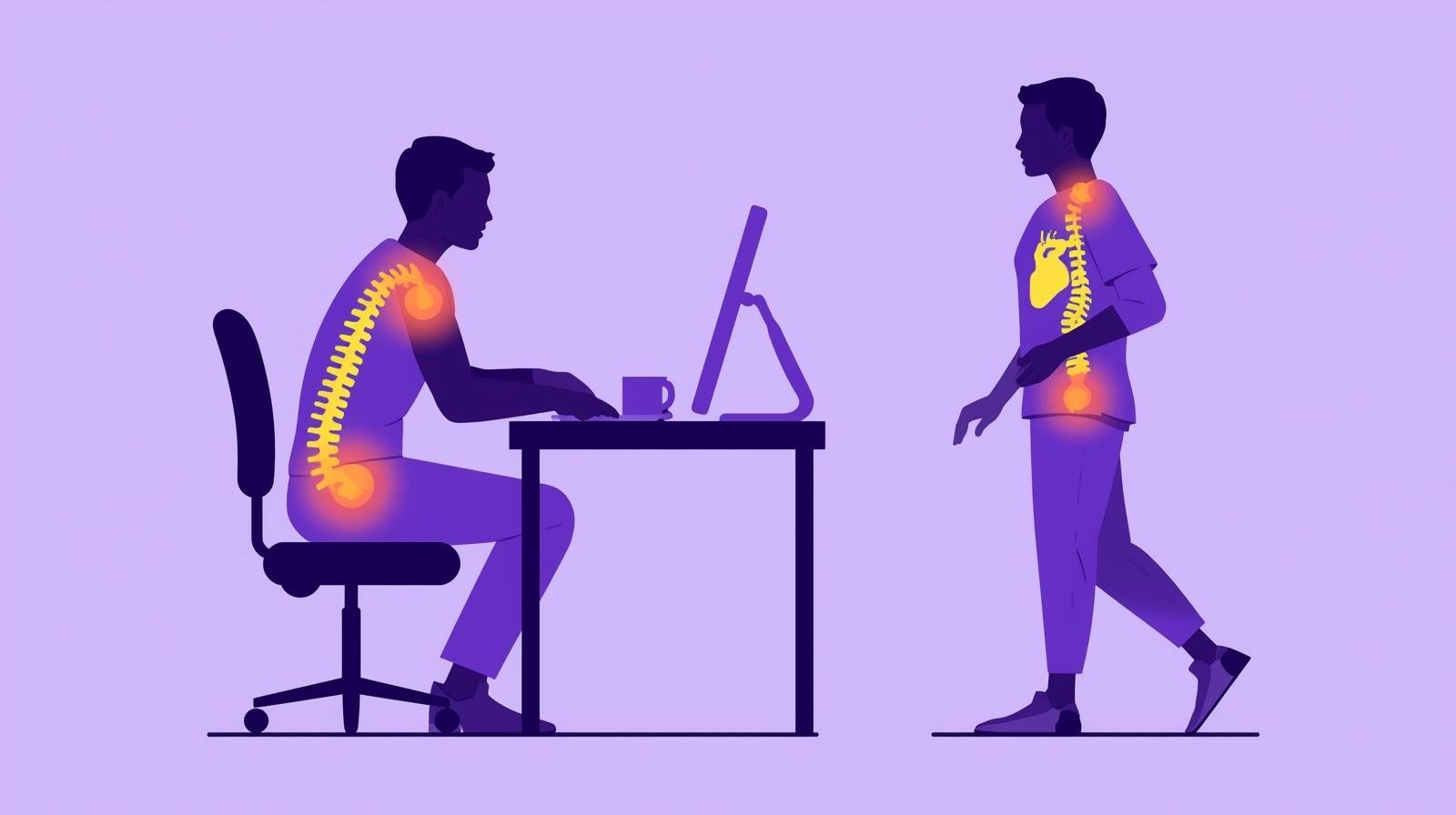

In recent years, health experts have been sounding the alarm on an unexpected modern hazard: prolonged sitting. You may have heard the phrase “sitting is the new smoking”,a bold comparison that draws attention to the hidden dangers of a sedentary lifestyle. While smoking directly damages the lungs, prolonged sitting can gradually harm your muscles, joints, heart, and spine in ways that are less obvious but equally concerning (Levine, 2015)

The reality is that our bodies are designed for movement. Human evolution equipped us to walk, squat, bend, and stand,not to remain motionless for eight or more hours each day. Yet, with the rise of desk jobs, remote work, and digital entertainment, millions now spend the majority of their waking hours in a chair.The consequences go far beyond stiff shoulders or mild discomfort. Research links long hours of sitting to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, certain cancers, and mental health challenges (Katzmarzyk et al., 2009). For the spine specifically, constant compression and poor posture can accelerate disc degeneration, weaken muscles, and trigger chronic pain syndromes. This article explores why sitting is compared to smoking, the scientific basis for these claims, the impact on back and spinal health, and, most importantly, practical steps you can take today to reverse the damage. By the end, you’ll understand exactly what your back needs instead of endless hours in a chair.

Why Sitting Is Compared to Smoking

The phrase “sitting is the new smoking” was popularized by Dr. James Levine of the Mayo Clinic, a leading researcher on sedentary behavior. While the comparison isn’t meant to be taken literally, sitting doesn’t flood your lungs with carcinogens, it emphasizes the widespread and underestimated health risks associated with being sedentary (Levine, 2015).

The Origin: The analogy emerged in public health discussions to highlight that, much like smoking in the mid-20th century, sitting is a socially accepted habit with serious, long-term consequences that many ignore.

The Research Link: Multiple studies have shown that people who sit for more than six to eight hours daily have higher rates of heart disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and premature death,even if they meet recommended exercise guidelines (Katzmarzyk et al., 2009). This mirrors smoking’s profile as a risk factor that operates independently from other lifestyle choices.

Statistical Comparisons:

- A meta-analysis in The Lancet estimated that physical inactivity accounts for 5.3 million deaths annually, comparable to the global mortality attributed to smoking (Lee et al., 2012).

- Sedentary individuals have a 49% greater risk of premature death compared to active individuals (Biswas et al., 2015)

- Expert Opinions: While some scientists caution against equating sitting directly with smoking in terms of toxicology, they agree that the public health message is valid: sitting too much is harmful, and the solution,more movement,needs to be built into daily life.

In essence, the phrase works as a wake-up call. It’s not meant to scare without reason, but to reframe how we think about everyday habits. Just as smoking prevention became a cornerstone of modern health campaigns, reducing sedentary time could become one of the most important wellness strategies of the 21st century.

The Science Behind the Health Risks of Sitting

The damage from prolonged sitting begins at the cellular level.

- Reduced Calorie Burning: When seated, large postural muscles in the legs and core remain mostly inactive, drastically lowering energy expenditure. With time, this reduced calorie burn contributes to weight gain and metabolic dysfunction (Hamilton et al., 2007).

- Poor Blood Circulation: Sitting compresses blood vessels in the legs, slowing circulation and increasing the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Reduced circulation also means less oxygen and nutrients reach spinal tissues, impacting disc health.

- Spinal Compression and Muscle Weakening: Sitting increases pressure on lumbar discs by up to 40% compared to standing (Nachemson, 1976). Over months or years, this can lead to disc bulges, herniations, and early degenerative changes. Meanwhile, core and glute muscles weaken, reducing their ability to stabilize the spine.

Chronic Disease Risks:

- Heart Disease: Sedentary time impairs fat metabolism, raising LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

- Type 2 Diabetes: Sitting decreases insulin sensitivity within hours, promoting elevated blood sugar (Dunstan et al., 2012).

- Obesity: Less movement means fewer calories burned, often paired with increased snacking during screen time.

- Certain Cancers: Studies link prolonged sedentary behavior to increased risk of colon, breast, and endometrial cancers (Lynch, 2010).

Mental Health Implications:

Prolonged sitting correlates with higher rates of depression and anxiety, partly due to reduced physical activity’s impact on neurotransmitter regulation and social engagement (Teychenne et al., 2010).

Example:

Consider a typical office worker, eight hours at a desk, an hour commuting, and two to three hours watching TV at night. That’s 11–12 hours of sitting daily. Over a decade, this lifestyle quietly erodes metabolic health, muscular strength, and spinal resilience.

The science is clear: prolonged sitting is not merely “doing nothing”, it actively disrupts multiple physiological systems, accelerating wear on the body much like an unhealthy diet or chronic stress would.

The Impact of Sitting on Your Back and Spine

While the entire body suffers from excessive sitting, the spine bears a unique burden.

- Changes in Spinal Curvature: Extended sitting, especially in poor posture, can flatten the lumbar curve or exaggerate thoracic rounding, shifting the spine out of its neutral alignment. This creates uneven pressure on vertebrae and discs.

- Effects on Lumbar Discs and Vertebrae: The lumbar spine acts as a shock absorber. In sitting, discs are under higher pressure, especially when leaning forward. With time, the gel-like nucleus inside each disc can push outward, leading to bulging or herniation.

- Postural Imbalances: “Forward head posture” and “rounded shoulders” are common adaptations to hours of screen use. These shifts strain neck muscles, compress cervical discs, and alter the body’s center of gravity.

- Links to Chronic Back Pain: A 2018 study found that over 54% of office workers reported weekly lower back pain, with sedentary time as a major predictor (Shrestha et al., 2018).

Case Example:

Emma, a 35-year-old accountant, began experiencing low back stiffness after switching to remote work. Without a proper chair or desk setup, she slouched more often. Within a year, MRI scans revealed early disc degeneration, something usually seen decades later.

Prolonged sitting doesn’t just “make your back sore.” It can structurally change your spine, weaken stabilizing muscles, and set the stage for chronic pain that limits daily life.

What Your Back Actually Needs Instead of Your spine thrives on movement, variety, and muscular support.

- Spinal Mobility and Flexibility: Discs rely on movement to circulate nutrients. Without it, disc tissue dehydrates and stiffens. Daily stretches like cat-cow or gentle spinal twists help maintain elasticity.

- Core and Back Muscle Strength: A strong core distributes load evenly and prevents overstrain on spinal joints. Exercises like planks and bird dogs activate deep stabilizers that protect the lower back.

- Movement for Disc Health: Even a two-minute walk boosts blood flow and nutrient delivery to spinal tissues. Alternating between sitting, standing, and light activity keeps discs hydrated and resilient.

Daily Habits:

- Stand during phone calls.

- Take the stairs instead of the elevator.

- Use a small water bottle so you refill it more often.

Active Sitting: This involves subtle movements while seated,such as using a stability ball or dynamic chair,to keep core muscles engaged.

The bottom line: your back needs variety, strength, and mobility,not hours of static pressure.

Practical Back-Friendly Solutions for Desk Workers

Ergonomic Workstation Setup:

- Desk height: Elbows at 90 degrees, forearms parallel to the floor.

- Chair: Lumbar support, adjustable height, and seat depth.

- Monitor: Top of the screen at eye level to prevent neck strain

Incorporating Movement:

- Standing desks allow alternating positions.

- Walking meetings promote circulation and creativity.

- Stretch breaks every 30–45 minutes.

Back-Strengthening Exercises:

- Planks (core stability)

- Bridges (glute activation)

- Wall angels (posture correction)

Posture Tips:

- Shoulder rolls every hour.

- Chin tucks to combat forward head posture.

- Use lumbar cushions for support

Movement Reminder Tools:

Apps like Stretchly or smartwatch alerts encourage regular breaks.

Example Routine:

Every hour: 40 minutes sitting, 15 minutes standing, 5 minutes moving.

Long-Term Lifestyle Adjustments for Spine Health

Balancing Sitting, Standing, and Walking Time

One of the most impactful shifts you can make is changing your time ratios between sitting, standing, and moving. Research suggests that for every 30 minutes spent sitting, you should aim for at least 5–10 minutes of movement (Benatti & Ried-Larsen, 2015).

Why It Matters:

Sitting for extended periods compresses the lumbar discs, decreases blood flow, and reduces nutrient delivery to spinal tissues. Alternating positions allows the spine to decompress and encourages natural movement patterns that nourish discs and strengthen supportive muscles.

Practical Implementation:

- Pomodoro Movement Method: Work for 25 minutes, then take a 5-minute break to stand, stretch, or walk.

- Hour Ratio Goal: Aim for 40 minutes of sitting, 15 minutes standing, and 5 minutes moving each hour.

- Standing Desks: Adjustable desks allow you to easily alternate between sitting and standing without disrupting workflow.

Example:

Sarah, a 42-year-old graphic designer, began standing for half of each workday and walking during lunch breaks. Within 6 weeks, her chronic lower back ache reduced significantly, and she reported higher afternoon energy levels.

Incorporating Regular Physical Exercise

Weekly Exercise Guidelines:

The World Health Organization recommends at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly, along with two or more days of muscle-strengthening exercises.

Why It Helps the Spine:

- Strengthens postural muscles, reducing load on the spine.

- Improves flexibility and range of motion, reducing stiffness.

- Enhances circulation, delivering nutrients to spinal discs.

Best Spine-Friendly Activities:

- Swimming: Low-impact, full-body strengthening.

- Yoga: Improves flexibility, balance, and posture awareness.

- Pilates: Builds core stability, essential for spinal alignment.

- Brisk Walking: Promotes circulation without excessive spinal loading.

Avoiding Exercise Mistakes:

- Jumping into high-impact workouts without building core strength first.

- Ignoring proper form during strength training.

- Skipping warm-ups and cool-downs.

Core Strength as a Daily Priority

Your core muscles, including the transverse abdominis, obliques, pelvic floor, and erector spinae, are the natural brace for your spine. Without adequate core strength, your vertebrae and discs take more mechanical stress.

Daily Core Activation Routine

Plank Variations: Front, side, and reverse planks for stability.

- Dead Bug Exercise: Strengthens deep abdominal muscles without stressing the back.

- Bird Dog: Improves balance and engages spinal stabilizers.

Why Daily Core Work Beats Weekly Workouts:

These muscles work all day to support your posture. Training them daily conditions them to endure long periods of sitting or standing without fatigue.

Conclusion

Prolonged sitting is a silent health hazard, gradually eroding your spinal health, weakening muscles, and increasing chronic disease risk. The good news is that small, consistent changes can protect your back and overall well-being. Stand more, move often, strengthen your core, and make your workspace spine-friendly. Your future self will thank you.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How many hours of sitting a day is harmful?

Studies show that sitting for more than six to eight hours a day is linked to a higher risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and even certain cancers (Katzmarzyk et al., 2009; Biswas et al., 2015). What’s more concerning is that these risks persist even if you exercise regularly, meaning an hour at the gym won’t fully undo eight hours at a desk.

The real danger lies in uninterrupted sitting. When you remain seated for long stretches, your muscles become inactive, your calorie burn drops, and spinal discs experience constant pressure. Over time, this leads to postural imbalances, back pain, and reduced metabolic health.

To minimize harm, experts recommend taking movement breaks every 30–45 minutes. This can be as simple as standing, stretching, or walking for two minutes. The World Health Organization (2020) also suggests combining sitting reduction with at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week.

Tip: Use tools like a smartwatch reminder or a free break-timer app to ensure you never sit for more than an hour without moving.

2. What exercises can strengthen the back for desk workers?

For desk workers, back health depends on strengthening the core muscles (abdominals, obliques, lower back) and improving spinal flexibility. Strong core muscles stabilize the spine, reduce the risk of injury, and help maintain healthy posture throughout the workday.

Some effective exercises include:

- Planks – Strengthen the entire core, improving spinal stability.

- Bridges – Activate the glutes and lower back to counteract sitting-related muscle weakening.

- Cat-Cow Stretch – Improves spinal flexibility and relieves stiffness.

- Wall Angels – Corrects rounded shoulders and promotes better posture.

- Bird Dogs – Strengthen lower back and improve balance.

Aim for 10–15 minutes of these exercises three to five days a week. You can break them into “movement snacks” during the workday, doing a 2–3 minute set during a coffee break or after finishing a task

Research shows that incorporating just 5 minutes of targeted strengthening exercises daily can significantly reduce back pain among office workers (Shrestha et al., 2018).

3. How often should you take breaks from sitting?

The ideal break schedule is to move every 30–45 minutes. Short, frequent breaks are far more effective than one long stretch of exercise at the end of the day. Even 1–3 minutes of light movement helps boost blood flow, wake up dormant muscles, and relieve pressure on your spine.

One popular approach is the 20-8-2 rule: For every 30 minutes, spend 20 minutes sitting, 8 minutes standing, and 2 minutes walking or stretching. This method, supported by ergonomic research, encourages variety in posture and reduces the risk of stiffness and muscle imbalances.

Micro-break activities can include:

- Walking to refill your water bottle

- Doing shoulder rolls or neck stretches

- Standing while making phone calls

- Performing seated leg lifts or ankle circles

Incorporating these small bursts of movement also improves mental alertness and productivity, making it a win for both your body and your work performance.

4. Can good posture offset the risks of prolonged sitting?

Good posture, neutral spine, shoulders relaxed, and feet flat on the floor significantly reduces strain on your back and neck. However, posture alone cannot fully offset the risks of prolonged sitting.

Even with perfect posture, muscles still weaken, calorie burn remains low, and blood circulation slows during extended sitting periods. This is why experts stress movement variety, switching between sitting, standing, and walking, rather than simply “sitting better.”

Think of posture as damage control, not a full solution. A spine in good alignment is less prone to pain and injury, but it still needs movement to stay healthy. For best results:

- Maintain good posture while sitting.

- Change positions often

- Stand or walk at least once every 30–45 minutes.

This combined approach is what truly protects long-term spine health.

5. What are the first signs of sitting-related back problems?

Early signs of back issues from prolonged sitting often appear subtly and are easy to ignore, until they become chronic. Common symptoms include:

- A dull ache or stiffness in the lower back after sitting for a long period

- Tightness in the hips or hamstrings

- Neck and shoulder tension from forward head posture

- Discomfort when standing up after extended sitting

- Reduced spinal flexibility or difficulty bending forward

If these symptoms occur frequently, it’s a sign your spine and supporting muscles are under strain. Left unaddressed, they can develop into more serious conditions such as herniated discs, sciatica, or chronic postural syndrome.

Early intervention is key. This may include adjusting your workstation ergonomics, adding core-strengthening exercises, and taking regular movement breaks. The earlier you act, the easier it is to reverse the damage and restore spinal health.

Reference

- Booth, F. W., Roberts, C. K., & Laye, M. J. (2012). Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Comprehensive Physiology, 2(2), 1143–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c110025

- Katzmarzyk, P. T., Church, T. S., Craig, C. L., & Bouchard, C. (2009). Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(5), 998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930355

- Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. (2012). Letter to the editor: Standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviours.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 37(3), 540–542. https://doi.org/10.1139/h2012-024

- Shrestha, N., Kukkonen-Harjula, K. T., Verbeek, J. H., Ijaz, S., Hermans, V., & Bhaumik, S. (2018). Workplace interventions for reducing sitting at work. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6(CD010912). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010912.pub3